Can we solve the ag labor shortage?

Finding enough qualified labor in agriculture is going to get lots tougher, unless folks take deliberate, creative action. First in a series that looks at fixing the ag labor shortage.

August 5, 2019

Imagine America without a third of its ranchers and farmers.

That’s the picture in the next couple of decades, based on producer age.

According to the 2017 Census of Agriculture released last spring, there were 3.4 million producers on 2.04 million farms and ranches.

“Number of producers is the total count of producers involved in decisions for the operation reported by the respondent,” according to the ag census.

Of those 3.4 million producers, 33.94% were 65 years old or older; 11.65% were at least 75 years old. Spun differently, ownership of a sizable chunk of U.S. agricultural production is likely to change hands over the next 10 to 25 years.

The hired labor force in agriculture is aging, too. According to the USDA Economic Research Service (ERS), the average age of hired farm laborers rose from 35.8 years in 2006 to 38.8 years in 2017, driven by aging foreign-born farm laborers. The labor force in this instance excludes managers, supervisors and other supporting occupations.

On the other side of the scale, just 8.39% of producers were 34 years old or younger.

Overall, the average age of all U.S. farm producers in 2017 was 57.5 years, which was 1.2 years older than in the 2012 ag census.

“If the current agricultural workforce — the majority of which is foreign-born — is not replenished by people who are interested in doing farm work even when they have other employment options, then the supply of farm labor will dwindle, and the average age of the agricultural workforce will rise,” ERS analysts explain in a bulletin published last year, “Farm Labor Markets in the United States and Mexico Pose Challenges for U.S. Agriculture.”

Certainly, production from some of the eldest producers will transition to the next generation, but evolution to this point has been for more people to leave production agriculture rather than remain a part of it.

“The vast majority of the U.S. labor force transitioned out of agriculture well before 1990,” according to the ERS publication. “By 1969, only 5% of the U.S. workforce was employed in agriculture. In 2017, agriculture accounted for about 13% of total employment in Mexico, compared with 1.5% in the United States.”

More production from fewer hands

Of course, the lower quantity of operations and producers continues to churn out ever more production, thanks in part to economic efficiencies of scale.

Ranches and farms with sales of $5 million or more made up fewer than 1% of all operations in the latest ag census, but 35% of all sales. Operations with sales of $50,000 or less accounted for 76% of the ranches and farms, and 3% of the sales.

The same sort of concentration exists for beef cattle operations. There were 729,046 operations with beef cows in the ag census. Of those, 576,735 operations (79.1%) had herds of 49 head or fewer, totaling 8.6 million beef cows — which represented 27.2% of the total beef cow herd (31.43 million head). Those operations accounted for 20.8% of sales, at $6.37 billion.

At the other end of the spectrum were 5,938 operations (0.81%) with herds of 500 or more beef cows. Those operations accounted for 5.47 million beef cows — 17.2% of all beef cows — and 21.5% of all sales, at $6.7 billion.

Tech helps motivate, makes efficiency possible

Whether it was the first iron-wheeled tractor, growth implants, fixed-time artificial insemination or precision planting, technology enables more production from fewer resources, often requiring less total overall labor. As necessary labor gets scarcer, the vicious circle continues as decision-makers look for ways to fill the gap, often with new or modified technology. Robotic milking parlors come to mind.

Along the way, the narrow economic margins associated with commodity businesses make for lousy economic incentive when it comes to encouraging nonowners to be part of agricultural production.

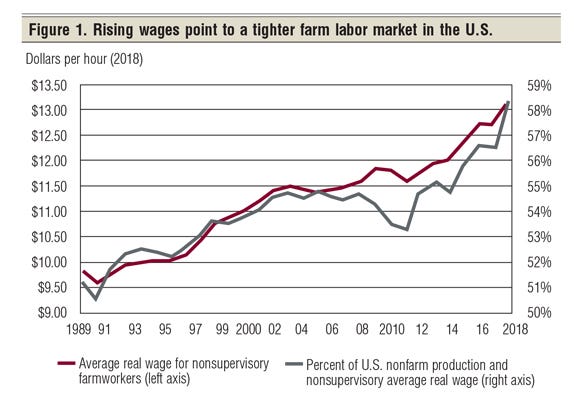

For instance, although increasing in recent years, the average real wage for nonsupervisory farmworkers in 2018 was a little more than $13 per hour, according to ERS (Figure 1). That was about 58% of the non-farm production, nonsupervisory average real wage. According to the most recent semiannual Farm Labor report from USDA, the average wage for hired livestock workers in April was $13.61 per hour.

In fact, you can argue that some ranch hands and farmworkers subsidize production agriculture by accepting lower wages than they could obtain elsewhere, in order to remain in production agriculture — because that’s who they are.

Some rural communities rightfully trumpet the need for more jobs and economic development, while some ranches and farms in those same communities would settle for having enough qualified workers to fill the jobs they already have.

Immigrants less interested in ag

Until recent years, immigrant labor — primarily Mexican immigrant labor — was the U.S. agriculture’s answer to bridging workforce gaps for seasonal work in labor-intensive sectors like fruit and vegetable production; and for nonseasonal workers in livestock sectors such as cattle feeding, beef packing and dairy production.

Now, fewer of them are interested in working on the production side of the fence.

“Today, after decades of expanding agricultural production and increasing immigration from rural Mexico to U.S. farms, the supply of farmworkers from Mexico is declining, and the pace of unauthorized immigration from Mexico has slowed substantially,” say authors of the ERS publication.

“Several scholars of Mexican migration have concluded that unauthorized immigration from Mexico is no longer keeping pace with the rate at which unauthorized immigrants are returning to Mexico. Between 2007 and 2015, the estimated number of unauthorized immigrants from Mexico living in the United States declined from 6.9 million to 5.6 million — a decline of 19%.

“Consistent with this finding, agricultural employers throughout the United States have reported increased difficulty in recent years in securing adequate supplies of labor at economically viable wages … expanding rural education in Mexico, as well as industrial growth in both Mexico and the United States, further reduces the number of Mexicans willing to work in agriculture in either country.”

For those who do want to immigrate and work in U.S. agriculture, even temporarily, and for those who want to hire them, good luck.

You don’t have to talk to more than a few attempting the process from either direction before hearing the nightmarish stories of conflicting rules and bureaucracy run amok.

The system is so broken that failure results from dedicating lots of time and money in an attempt to do things by the book.

No wonder that various estimates peg undocumented immigrants at about half of the U.S. agricultural workforce.

The American Farm Bureau Federation goes further, in its “Economic Impact of Immigration”: “At least 50% to 70% of farm laborers in the country today are unauthorized. Few U.S. workers are willing to fill available farm labor jobs.”

Incidentally, as fewer young immigrants choose to work in agriculture, the average age of immigrant farmworkers in the U.S. rose from 35.7 in 2006 to 41.6 years in 2017.

Future trends

Certainly, there can be enough motivated, qualified agricultural workers in the future.

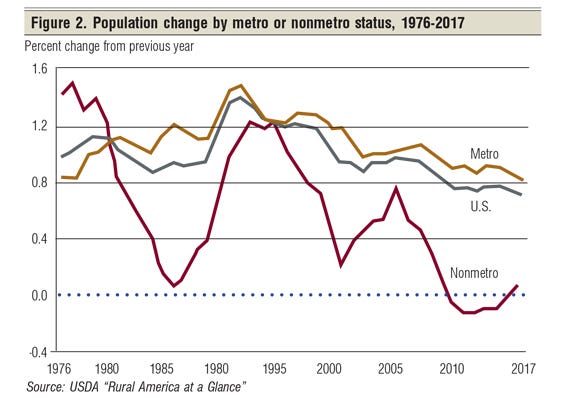

In fact, rural U.S. counties added population in 2016-17 for the first time in a decade, according to USDA’s “Rural America at a Glance” (Figure 2). Albeit slight, the increase was due to net migration rather than the net natural difference between births and deaths.

But having enough agricultural workers in the future favors taking deliberate action.

In some cases, the solution could be as simple as employers getting more proactive about recruiting, training and retaining workers. For that matter, helping young people see and understand the agricultural jobs in their midst can help.

For its part, the federal government created the Interagency Task Force on Agriculture and Rural Prosperity two years ago. Its call to action includes identifying rural employment needs, attracting available workers and providing necessary training and education.

There are more revolutionary ideas afloat, too, like Service-member Agricultural Vocation Education (SAVE) Farm, an organization aiming to provide military veterans and returning military service members with a transitional pathway to careers in agriculture.

BEEF will explore these and other issues related to the growing shortage of rural labor in this exclusive BEEF series.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)