Bruised beef carcasses = bruised bottom line

A study of bruised carcasses in packing plants reveals the surprising extent of the problem.

November 6, 2018

By Helen Kline

Carcass bruising has long been an issue in fed cattle, cull cow and bull packing plants. Lately, however, the incidence of bruised carcasses has been rising.

That’s a problem, because bruises can be the cause of economic loss in the beef industry, and they can also be indicators of potential animal welfare concerns during pre-slaughter animal handling in the cattle supply chain.

To determine the extent of carcass bruising and its effect on the beef industry, Colorado State University collaborated with a major beef packer to study cattle handling and carcass bruising from 2017 to 2018 in fed beef and cull cow commercial slaughter facilities. Researchers went to five facilities across the nation and collected extensive data to understand how and why cattle may be getting bruised during the marketing process.

Information was collected on cattle trailer type, trailer compartment, pre-harvest animal metrics (such as lameness and body condition), bruise trim prevalence, bruise location, bruise color, bruise trim weights and sex class. This study’s aim was to assess trailers and trailer compartments as a critical control point for bruising in the livestock supply chain.

A selection of cattle from each trailer observed were individually identified and followed through the entire slaughter system (a total of 617 cattle were marked individually). By doing this, the research team was able to record events during unloading and transport for these specific animals to use to start to uncover how or why these cattle may have been getting bruised. For these individual cattle, the team was able to score specific bruise location in addition to actually identifying if any bruised meat was trimmed off during the slaughter process.

Results indicate that the most heavily bruised carcass areas are also some of the most valuable carcass regions — and often the ones that needed to be trimmed. Visual carcass bruising was 28% in total. Categorized by cattle type, 52.8% of the cow carcasses were visibly bruised, 64.3% of the bull carcasses were visibly bruised and 36.5% of the fed steer or heifer carcasses were visibly bruised.

Bruise trim loss occurred on 56.4% of the marked, preselected carcasses from all five facilities. If the preselected carcasses were visibly bruised, then 76.5% of the time the team also collected bruise trim loss from those carcasses.

The ‘iceberg effect’

However, 41.7% of the carcasses on which the team could not visibly see bruising also had bruise trim loss. We call this the “iceberg effect.”

This iceberg effect occurred at each harvest facility. These areas on the carcass appeared as light pink hues that were too light in color to score with the bruise color chart. However, when these areas were trimmed, they revealed deep tissue bruises below the surface that team members were unable to see before.

These deep tissue bruises were going undetected approximately 24.1% of the time. Categorized by cattle type, 72.9% of preselected cow carcasses experienced bruise trim loss, 76.9% of preselected bull carcasses experienced bruise trim loss and 49.8% of preselected steer and heifer carcasses experienced bruise trim loss.

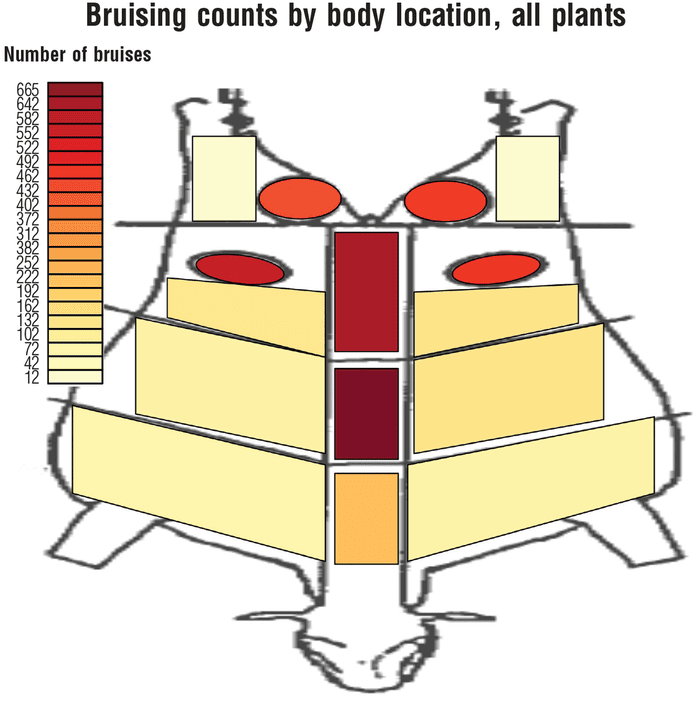

The regions of the carcass with the highest bruising incidence were the loin, hip, dorsal rib and round regions (Figure 1). This is in line with many of the previously reported studies.

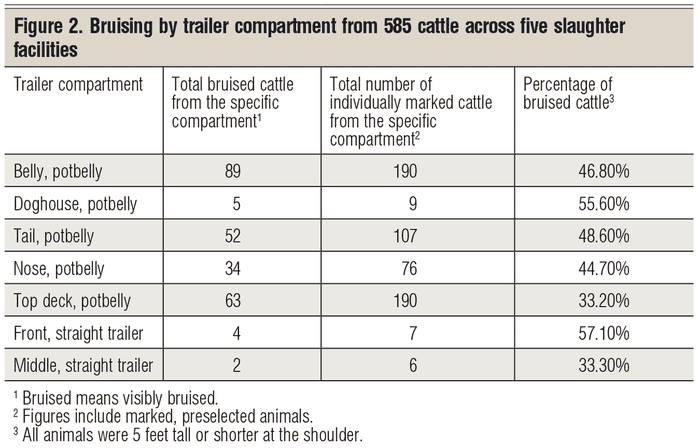

As shown in the figure, the darker the color for the region of the carcass, the more bruises were observed for that region. When the trailer compartments were compared for bruising prevalence, cattle transported in the “doghouse” (the small top compartment above the entrance and exit to the trailer) in potbelly trailers had the highest observed bruise frequency.

Cattle were least bruised in the potbelly trailer-style middle top deck compartment. Cattle in the middle top deck compartment were less likely to be bruised when compared with cattle in the middle bottom compartment (the belly).

Unfortunately, during this study the “straight” trailer style, with a single level and three compartments, was not observed as many times as the potbelly style of cattle trailer. A summary of all potbelly and straight trailer compartment bruising incidences can be found in Figure 2. Steers and heifers were less likely to be bruised than cows. However, there was not a notable difference between steers and heifers compared with bulls, or bulls compared to cows for bruising incidence.

Based on the results of this study, visual bruising assessment may not be the most accurate method to determine a bruising incidence rate for the beef industry. Deep tissue bruises are difficult to detect with visual assessment on the slaughter floor, and other methods may be needed to observe them.

The scientific community is still developing the methodology for detecting and aging bruises with more objective methods, but visual detection and the color cycle of a bruise (red, purple, blue, green, and yellow) are generally accepted.

Identifying the critical control points for bruising in the livestock supply chain is an ongoing and ever-improving process. By examining each step in the marketing process, we can evaluate the risk factors for bruising to hopefully reduce the amount of bruising seen at the slaughter facilities. To decrease bruising will take an industry-wide effort to improve animal handling and well-being throughout the beef supply chain.

Kline recently was awarded a doctorate from Colorado State University. This study was conducted under the advisement of Temple Grandin, professor at CSU, and Lily Edwards-Callaway, assistant professor at CSU as part of Kline’s doctoral dissertation.

You May Also Like

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)