thumbnail

Cattle Health

Health and performance of stressed calves can be improved with organic mineral sourcesHealth and performance of stressed calves can be improved with organic mineral sources

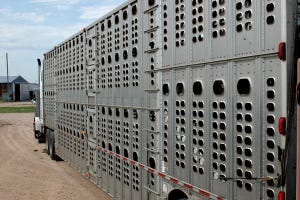

The stress of weaning and shipping calves can impact their health and growth. A study by Kansas State University found that feeding stressed calves organic minerals improved health and performance.

Subscribe to Our Newsletters

BEEF Magazine is the source for beef production, management and market news.

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)